Sponge cities and nature-based solutions

As a practitioner focused on designing public spaces and delivering nature-based solutions on projects around the world, it’s encouraging that some of the best solutions to climate challenges in our cities already exist. Think trees, parks, and ponds - a growing body of international research shows that nature-based solutions are more effective and less expensive than conventional concrete and other grey solutions to address climate-change risks, including heavier rains and more frequent storms in urban environments.

Around the globe, so called Sponge cities are known for their ability to mitigate flooding. Sponge cities have natural green and blue infrastructure which improves their ability to absorb rainfall. This is critical, as research from the World Economic Forum shows blue-green infrastructure is not only effective at managing water, but also 50 per cent more cost-effective, on average, than man-made alternatives, delivering 28 per cent more added value.

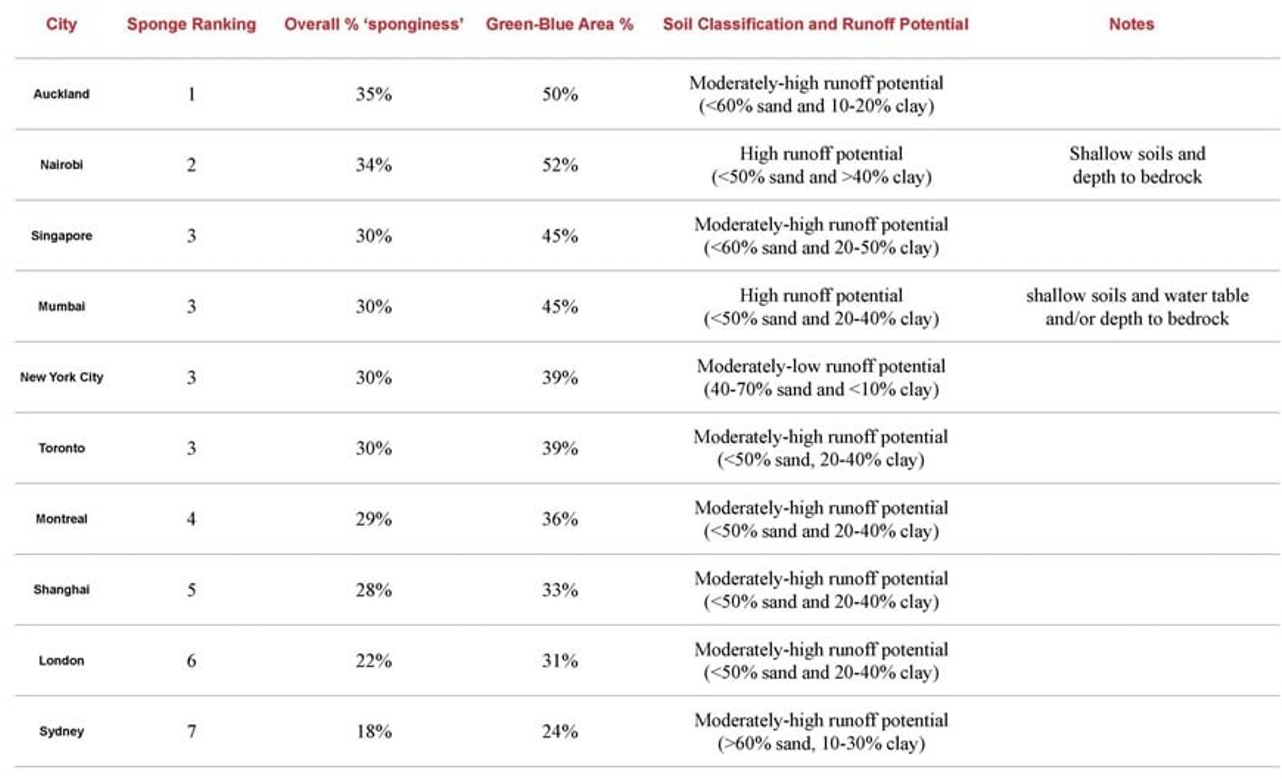

To support thinking around Sponge cities, colleagues in my consulting engineering firm Arup, have produced a 10-city Global Sponge Cities Snapshot – a global survey of the natural ability of cities to absorb rainfall. The report is based on Arup’s use of its proprietary Terrain digital tool to map the ‘sponginess’ of world cities, from London, England, and Cairo, Egypt, to Shanghai, China, and Sydney, Australia, based on satellite images of parks, trees and other natural structures in their central cores. To create the Sponge City Snapshot calculations, we use Terrain to apply machine learning and artificial intelligence techniques to accurately quantify the amount of green infrastructure (e.g., grass, trees) and blue (e.g., ponds, lakes), versus the amount of grey (e.g., buildings and hard surfaces) from satellite imagery. We then supplemented this analysis with insight on soil types and vegetation, enabling them to estimate how much rainwater would be absorbed in a defined heavy rainfall event. The cities were ranked based on these factors.

In North America, sponge cities in the survey include Toronto, Montreal, and New York. Toronto is among the world’s most ‘sponge-like,’ able to absorb rainfall and mitigate flooding that has become more common with climate change. The survey shows Toronto is far ahead of Sydney and London in terms of its “sponginess,” with its sponge rating of 30 per cent (compared to 18 per cent for Sydney and 22 per cent for London).

Toronto ranked third in the sponginess snapshots, just ahead of Montreal and tied with New York City, Singapore, and Mumbai. Over one quarter (29 per cent) of the land analyzed in Toronto is covered in trees. The snapshot shows Toronto’s ravines function as a network of urban green infrastructure which mitigates flooding risks. The city’s interconnected ravine system links with natural watercourses to receive, filter, and transport stormwater from urban landscapes to Lake Ontario. Toronto has already begun expanding blue-green infrastructure across the city, particularly along the lakeshore, where Arup has worked with the city and partners in the design of the Queens Quay waterfront revitalization, as well as new waterfront parks-Corktown Common, Aitken Place Park, and Love Park – which incorporate recreational spaces as well as natural water management features.

Montreal is making significant strides in managing stormwater because of its notable commitment to expanding green spaces, creating resilient parks and water squares, such as Fleur de Macadam, and replacing aging grey infrastructure. Our data shows the city’s sponginess ranking is boosted by the fact that its green spaces contain a high proportion of trees, including the iconic Mount Royal Park. The urban forest provides numerous co-benefits ranging from provision of natural habitat to reduction of urban heat island effects, promotion of recreation to nurturing wellbeing.

We’ve learned cold climate cities like Montréal and Toronto must design nature-based solutions to better absorb water, acting like a sponge even when temperatures drop below freezing. Well-designed blue-green infrastructure can absorb water even in cold conditions. Healthy soil and root ecosystems create a layer of heat, trapped between the soil and snow, becoming a more effective sponge and contribute to the city’s resilience.

Looking beyond Canada, as the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) predicts that water-related risks will increase with every degree of global warming, we know there are around 700 million people currently living in regions where maximum daily rainfall has increased. It’s time we take additional action to move beyond concrete interventions and instead look increasingly to nature for solutions to climate-related challenges.